Image supplied by Parliamentary Archives.

The Times newspaper proprietors sued the publisher John Lane (1854-1925) for copyright infringement. The litigation centred on the legality of a book published by Lane entitled “Appreciations and Addresses delivered by Lord Rosebery” (1899) that allegedly copied almost verbatim a series of reports previously published in the London paper. Ironically, what made this action peculiar was a procedural subtlety: the absence of Lord Rosebery (1847-1929) as the claimant. Brought under the Literary Copyright Act of 1842, which protected “books”, the key issue became whether it was possible to view a report of a speech as a book of which the reporter was the author. Ultimately the case went to the House of Lords. The majority of the House of Lords (Earl of Halsbury L.C., Lord Davey, Lord James of Hereford, Lord Brampton) held that there was a copyright infringement, reversing the decision of the Court of Appeal and making the injunction perpetual. Lord Robertson dissented; he found it “difficult to understand what attribute of an author belongs to [the reporter]”

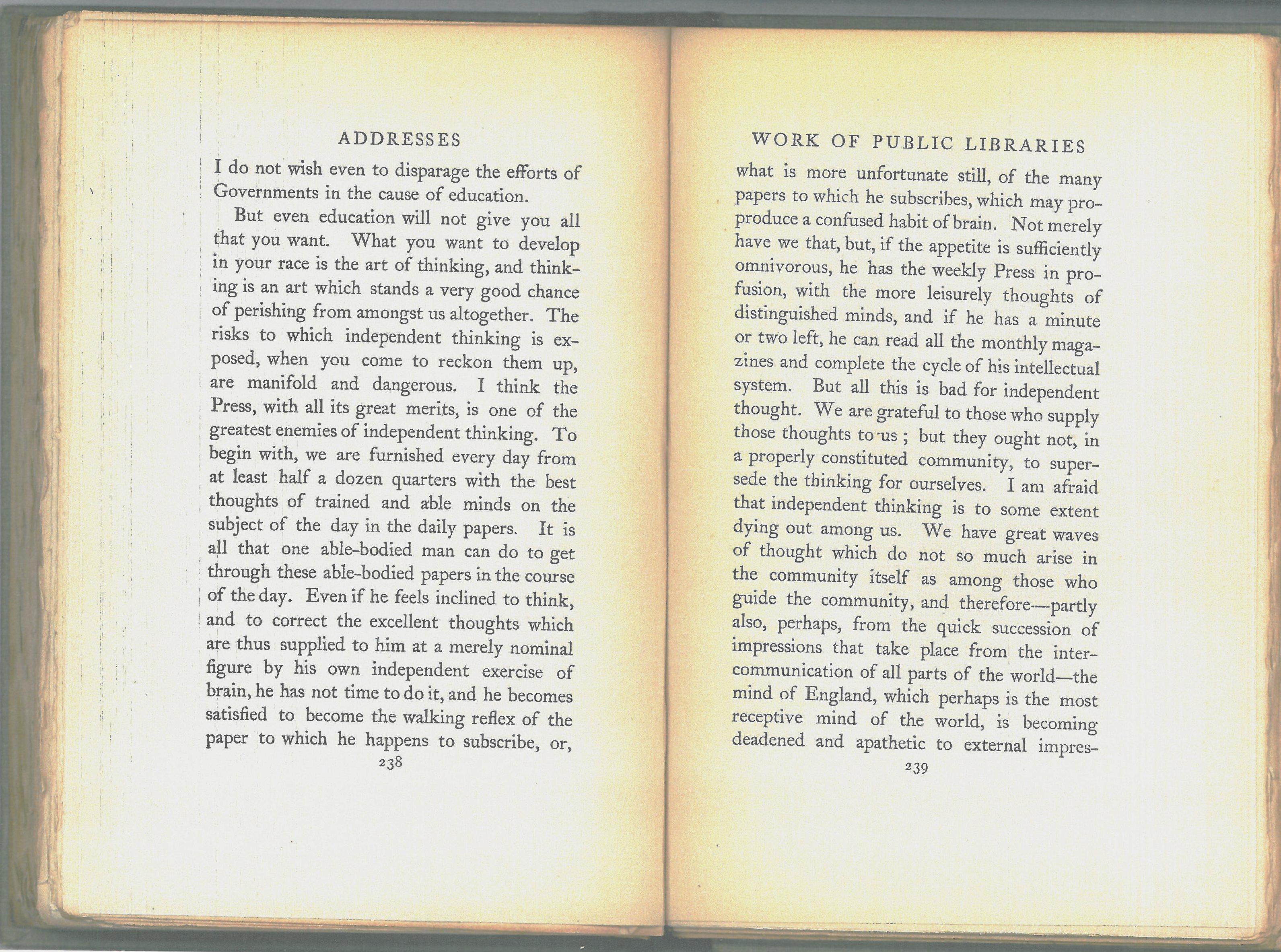

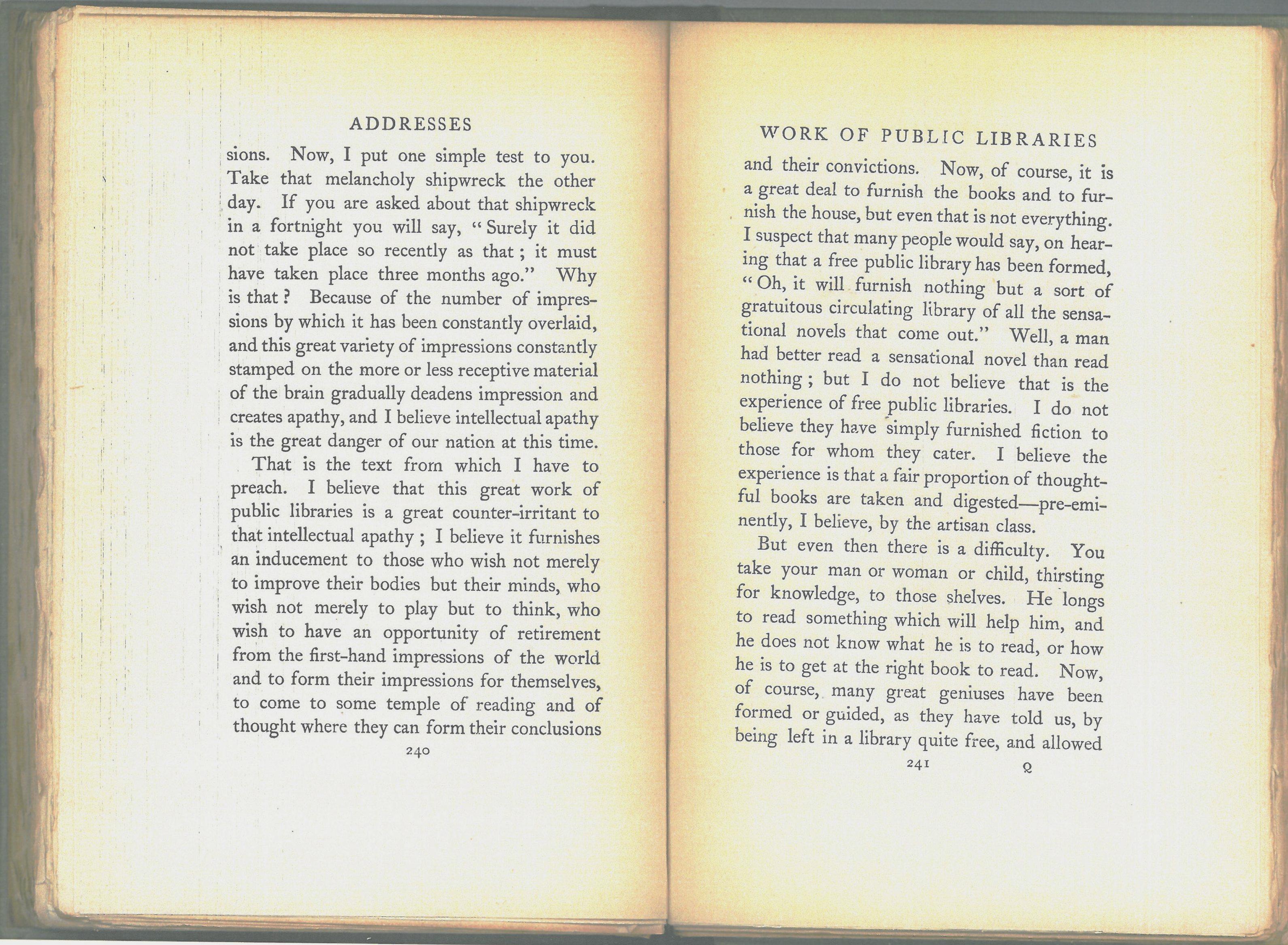

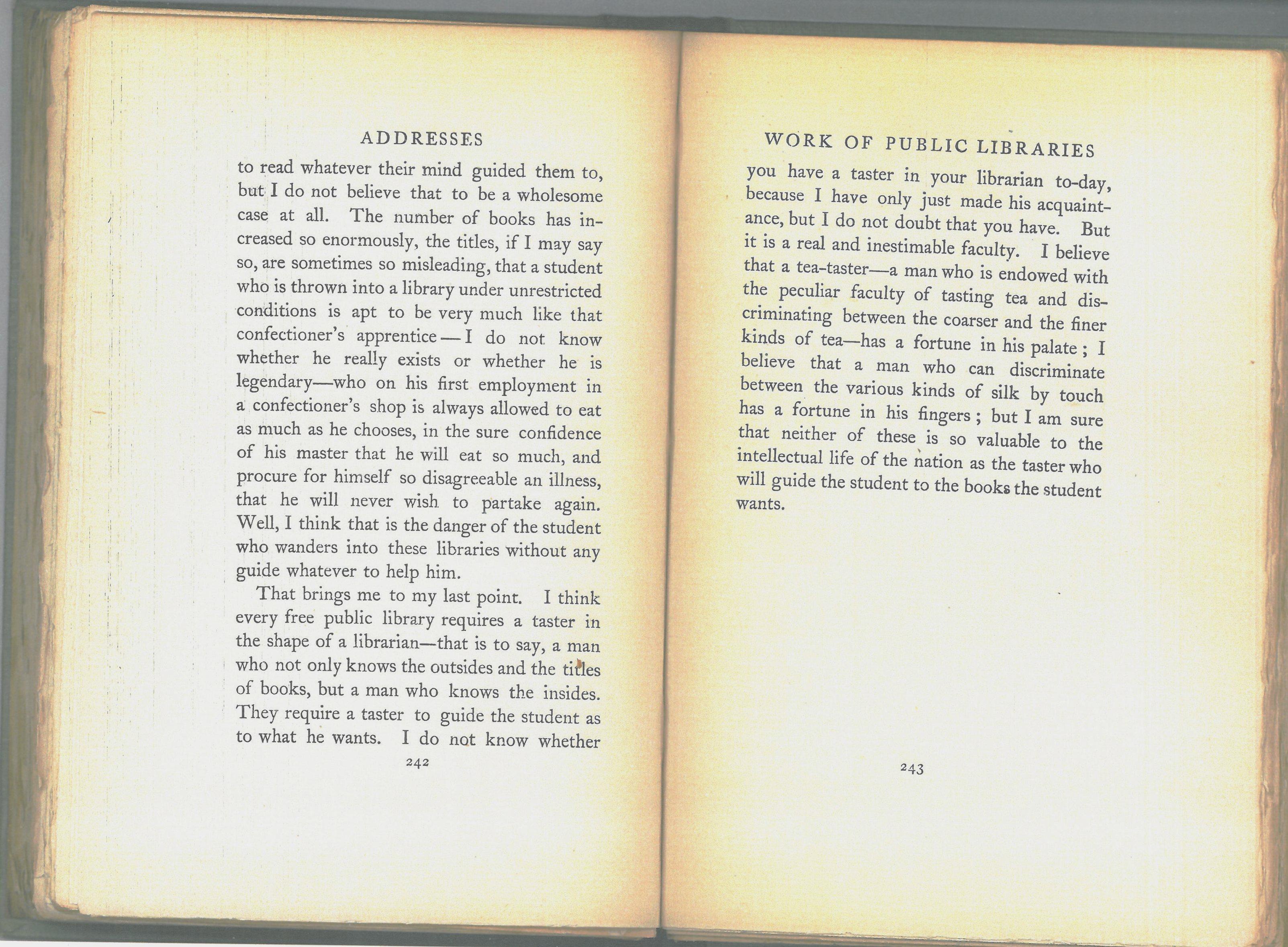

The case became a powerful example of the controversies surrounding the making of subjects and objects in British copyright law. Firstly, it illustrated how different kinds of copyright works could (or could not) emerge in relation to verbal and written record. Secondly, it showed how reporters’ labour may be significant to make them “authors” under copyright law. While the awkward position of the decision before the enactment of the Copyright Act (1911) facilitated doctrinal discussions around the validity of the case, its historical importance derives from its capacity to provide insights of the types of labour protected by copyright law. It is only by looking closely at the reports of the speeches (and comparing them with other reports of those same speeches), and considering the technological context (in particular, that at this time sound recording was very much a novelty), that one can appreciate how the Court could find the process of creating the reports to have involved labour, skill and judgment. Displayed here is a selection of images of the material litigated showing how the defendant's publication was taken "almost verbatim" from the reports previously published by The Times.

In 1911, the terms on which protection was offered were altered. Thereafter, protection was only available for “original” literary (etc) works. The decision in Walter v Lane was thereafter understood as setting the “originality” threshold, and was affirmed in cases such as Express Newspapers v News (UK) [1990] FSR 359 and Sawkins v Hyperion [2005] EWCA Civ 565 (where it was assumed to be good law). It seems unlikely that the reasoning of their Lordships can be found applicable in the post-Infopaq era. However, a close look at the fact raises important questions for the new European standard of originality: does a reporter who sets out to make a verbatim report of a speech exercise “creative choices” when he or she decided on punctuation, on whether to report the reaction of the audience, and so on? Are those choices of such a type that we can say that a report bears the “personal touch” of its author? For further analysis, see Nigel Gravells, ‘Authorship and Originality: The Persistent Influence of Walter v Lane'. (2007) 11 Intellectual Property Quarterly 267

Twitter

Twitter Email

Email