Image courtesy of the Wellcome Foundation Archives.

In 1902, Burroughs Wellcome and Co. (London) went to court against Thompson and Capper (Manchester and Liverpool) seeking an injunction to restrain them from passing off their goods as the goods of the plaintiffs by the use of the words “tabloid” or “tabloids”. The defendants not only denied having passed off their goods as the goods of the plaintiffs but they also retaliated by requesting the plaintiffs’ trade mark to be struck off the register.

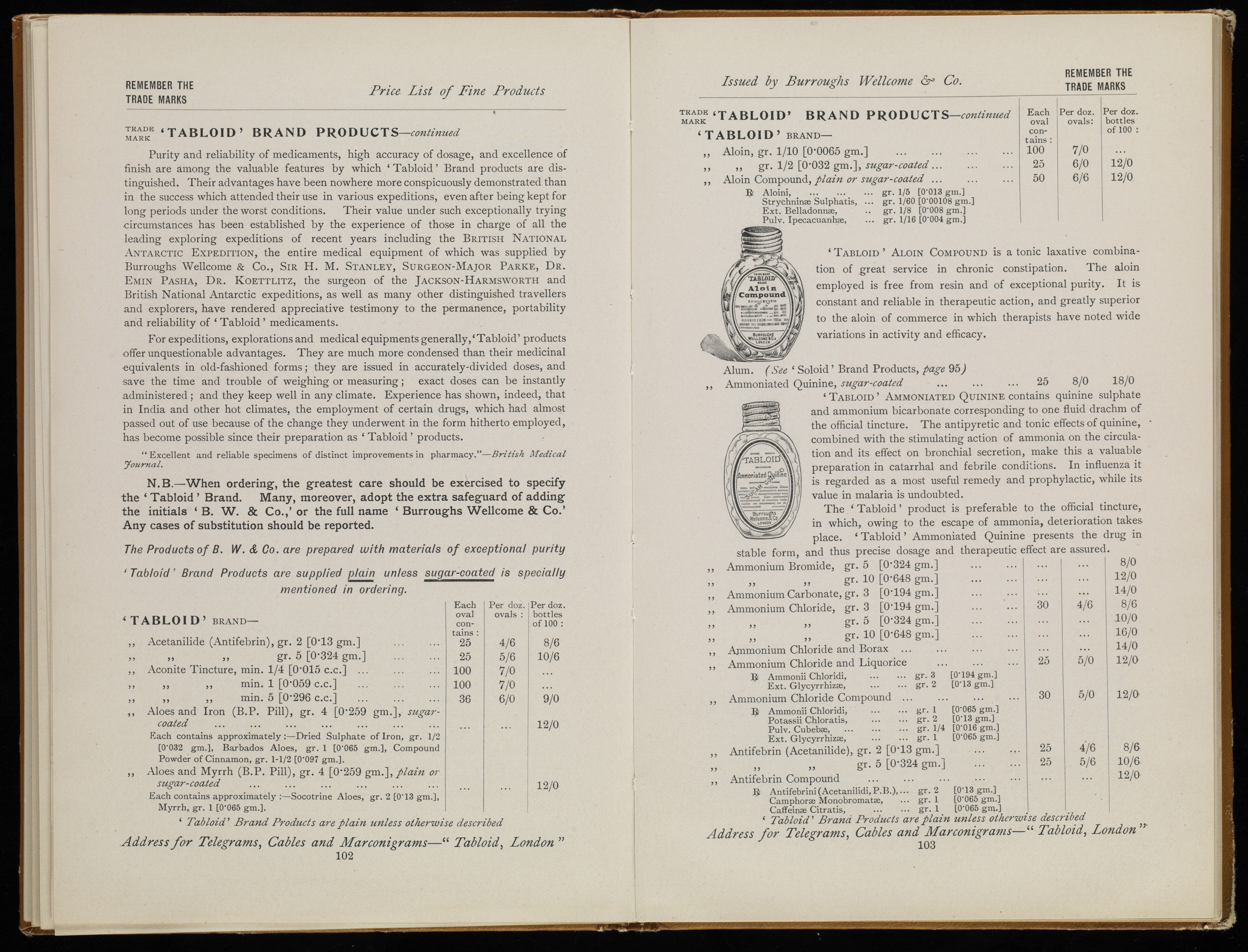

The type of misrepresentation argued by Burroughs Wellcome and Co. was the practice involving the substitution of drugs. In fact, the plaintiffs produced evidence that the defendants, when asked for “tabloid” or “tabloids”, supplied goods that were not of the plaintiff’s manufacture. According to them, the practice of substitution was unfair trading. What made this controversy particularly interesting was the underlying context from which it emerged, highlighting the professional tensions between medicine, nursing and pharmacy and showing how corporate trade mark strategies are embedded in circuits and networks (here London, Manchester and Liverpool). When Burroughs Wellcome and Co. was about the initiate the claim, the company was particularly afraid of the impact it could have in its dealings with Liverpool chemists that could perceive the case as an attack from London. The case illustrates the singular character of the pharmaceutical trade, articulated around different activities (prescribing and dispensing medicines) to be associated to different professions. Here we have included a document that reveals how the plaintiffs busied themselves to advertise the trade mark and how conscious they were of the menace to their trade by the practice of substitution. Price lists, diaries and promotional literature published by Burroughs Wellcome and Co. not only tried to call attention to the fact of the trade mark to nurses, doctors and chemists; they also warned them against substitution. This specific document displayed here was marked HSW-1 and was used by Sir Henry Solomon Wellcome (1853- 1936) in the declarations before the Patent Office and in the different disputes concerning the trademark “tabloid”.

After a seven days’ trial, Mr Justice Byrne decided that the defendants had been guilty of passing off or substituting other goods in place of the “tabloid” or “tabloids” made by the plaintiff and dismissed the defendant’s attempt to expunge the plaintiffs’ trade mark. In so doing, he granted an injunction to restrain the defendants from passing off goods not made by the plaintiffs in response or orders for “Tabloid” or “Tabloids”.

A few months later, the defendants appealed against the specific decision to dismiss the attempt to strike off the trade mark from the register. The litigation was therefore narrowed down as to whether or not “Tabloid” was a distinctive fancy word not in common use at the time of registration. That the counter-attack raised by the defendants was a strong one and that the whole litigation was extremely risky for the plaintiffs could be seen in at least two instances. Firstly, and before the action, the trade mark expert, Lewis Boyd Sebastian (1852-1926), recommended the plaintiffs to register a new “tabloid” trade mark consisting of a picture or a device with the corporate signature in case the mark was expunged. Secondly, the risk of the litigation can also be appreciated in the efforts the plaintiffs developed throughout the hearing to separate the history of the use of the “Tabloid” trade mark from the history of compressed drugs. This anxiety to separate the histories was an attempt to avoid the claim that the mark was or had become a common word.

The Court of Appeal (Lord Justice Vaughan Williams, Lord Justice Stirling and Lord Justice Cozens-Hardy) unanimously rejected the appeal and upheld the judgment of the Chancery Judge. It held that the word (“Tabloid”) was a distinctive fancy word at the time of registration (1884) and that it should not be removed from the register. In the course of the hearing, Lord Justice Vaughan Williams said that “the longer a trademark has been on the register the stronger the onus in favour of the person who has registered it, and the stronger the onus against the person seeking to remove it”.

The best historical account of the case is given in Roy Church and E.M Tansey’s Burroughs Wellcome & Co. Knowledge, Trust, Profit and the Transformation of the British Pharmaceutical Industry 1880-1940 (Lancaster: Crucible Books, 2007) especially, chapter 6.

Twitter

Twitter Email

Email