Images courtesy of the National Football Museum.

The flurry of cases since the new millennium began over whether there are intellectual property rights in football fixture lists – the Fixtures Marketing and Football Dataco cases that went to the CJEU – can be seen as important moments in the forging of a new pan-European copyright law, : see Eleonora Rosati, “Towards an EU-wide copyright? (Judicial) pride and (legislative) prejudice” Intellectual Property Quarterly, 2013, 1, 47-68. However, claims to rights over football fixture lists are nothing new. In fact, consideration of whether, and if so how, to leverage such compilations into a revenue stream for football clubs date back at least as far as the 1930s when a “war” broke out between the Football League and the flourishing companies offering “pools”.

The Football Association was founded in 1863, establishing a set of rules for the game, and later inaugurating a “challenge cup competition” in which all members could enter (“The F.A. Cup”). The Association had already permitted professionalization before The Football League, was founded in 1888. The primary goal of the League was to establish a fixture list. It began doing so with twelve clubs. The League expanded to a second division, and after the First World War to a Third. The game became hugely popular. For example the first FA Cup final to be staged at the new Wembley stadium in 1923 attracted twice the grounds capacity of 127,000. (See, Charles E Sutcliffe, The Story of the Football League (Preston: The Football League, 1939; S. Inglis, League football and the men who made it: the official centenary of the Football League, 1888–1988 (1988); Mark Clapson, A bit of a flutter: Popular gambling and English society c.1823-1961 (1992)).

Pools betting on the results of matches seems to have emerged in the 1920s. Punters would pay small sums to predict the results of football matches. [Explanation] Vernon Sangster (1899-1986) had established Vernons in Manchester in 1923 and John Moores had set up Littlewoods in Liverpool in 1924, and both businesses. By the mid-1930s, estimated expenditure on pools was in the region of £20 million, with 10 million punters (The Manchester Guardian, Oct 3, 1935).

Nevertheless, some clubs were in dire financial straits. It was thought that the pools were draining the game of money and patronage. Charles Edward (“C E”) Sutcliffe (1864-1939), who devised the fixtures and had been on the league management committee since 1898, led the campaign. According to one commentator, he was “offended, if not enraged, that these mushroom organisations should be feathering their nests at no cost on the work of others” (Obituary, The Guardian, Jan 12, 1939). Watson Hartley, and accountant, presented a proposal to the Football League Management Committee to rely on the copyright in the fixture lists as a basis for licensing their use, a strategy that it was anticipated might raise £60,000 (The Guardian, Dec 4, 1935). The opinion of “eminent counsel” was sought and “established” the question of copyright (The Guardian, Feb 21, 1936) (though the Football Pools Promoters’ Asssociation, formed in 1934 to defend the interests of pools companies, also said it had been “advised by leading counsel that there is no such infringement”: The Guardian, March 31, 1936).

However, the League’s strategy was rapidly transformed. Rather than issuing court proceedings., in February 1936 it was decided to withdraw the existing published fixture lists, and instead to reveal the teams that would play only on the Thursday before the games would be played (at that stage, always on Saturdays). The stated goal was not to negotiate but rather to bring “the menace” or “evil” of pool betting to an end (The Guardian, Feb 22, 1936). The whole matter was now suffused with concern over moral concern with gambling and its potential to corrupt the game (which had suffered a match-fixing scandal in 1915 in relation to the game between Manchester United and Liverpool). Indeed, the Football Association had supported a proposal to outlaw pools altogether in the Betting and Lotteries Bill of 1934, but the Government had dropped the proposal from the Act, though in 1936 it was being revived by R J Russell MP, Liberal National member for Eddisbury in Cheshire). The League ruled out licensing on the grounds that this would mean clubs had an interest in the existence and success of pools. Apparently 65 clubs voted in favour, 12 against while 8 abstained.

The strategy was no sooner announced than dissenters emerged, observingthat the policy of keeping the fixtures secret would cause real problems for supporters and the railway companies. Leeds United (led by Alderman A Masser) was the first club openly to express disagreement, but other clubs soon joined the revolt. Arthur Barrett of Blackburn Rovers called the new practice “absurd”, wile Birmingham City referred to it as “hasy”. As the League’s plan was implemented, it became clear the clubs were being damaged: fans boycotted games (The Guardian, Feb 27, 1936) and the gates were significantly down (The Guardian, March 2, 1936). At the same time, the pools companies developed strategies to deal with the late revelation of fixtures and denied that the League’s rearrangement of the fixtures was having much effect. By the 10 March the Football League ended the “war”, and the original fixtures were restored. Although negotiations seem to have started up with the pools companies, the moral objection to any arrangement continued to hold sway. The Football Association ruled that the clubs could not receive money from the pools companies without breaching the association rules (The Guardian, April 2, April 21, 1936). Even in 1938, an offer from the Pools promoters to give £5000 pa to the Jubilee Fund - a fund to support injured players and offer education - was rejected (The Guardian, Aug 24, 1938). At various times during the War, the League and FA both affirmed this stance.

After the war, the issue of the relationship between the Football League and the pools companies was revisited. In 1945, the League was offered £100,000 by the pools association but again declined (The Guardian, Oct 20, 22, 1945; Jan 21, 1955). Nevertheless, in submissions to a Royal Commission on Lotteries, Betting and Gaming in 1946, the FAs attitude was rather non-interventionist. Soon after the Players’ Union suggested that there could be a “National Football Pools”, which would plough its profits back into the game: The Guardian, Feb 20, 1947. WC Cuff responded that he though the pools were “a social evil”. By the 1950s, attitudes were changing and it was though monies raised could be used for ground development without compromising the clubs.

In the 1950s, two events were to have a particular bearing on their decision to litigate: the passing of a new copyright law for Great Britain and Northern Ireland (1956) and the Football League's presidential elections held in 1957. Arguably, the expectations surrounding the enactment of the law had an impact on the new managerial decisions taken. One year after the enactment of the Copyright Act (1956), the League, led by its new elected president, Sir Joseph Richards (1888-1968) and its secretary, Alan Hardaker (1912-1980) prepared a test case. On this occasion, it seems, the motivation was purely pecuniary.

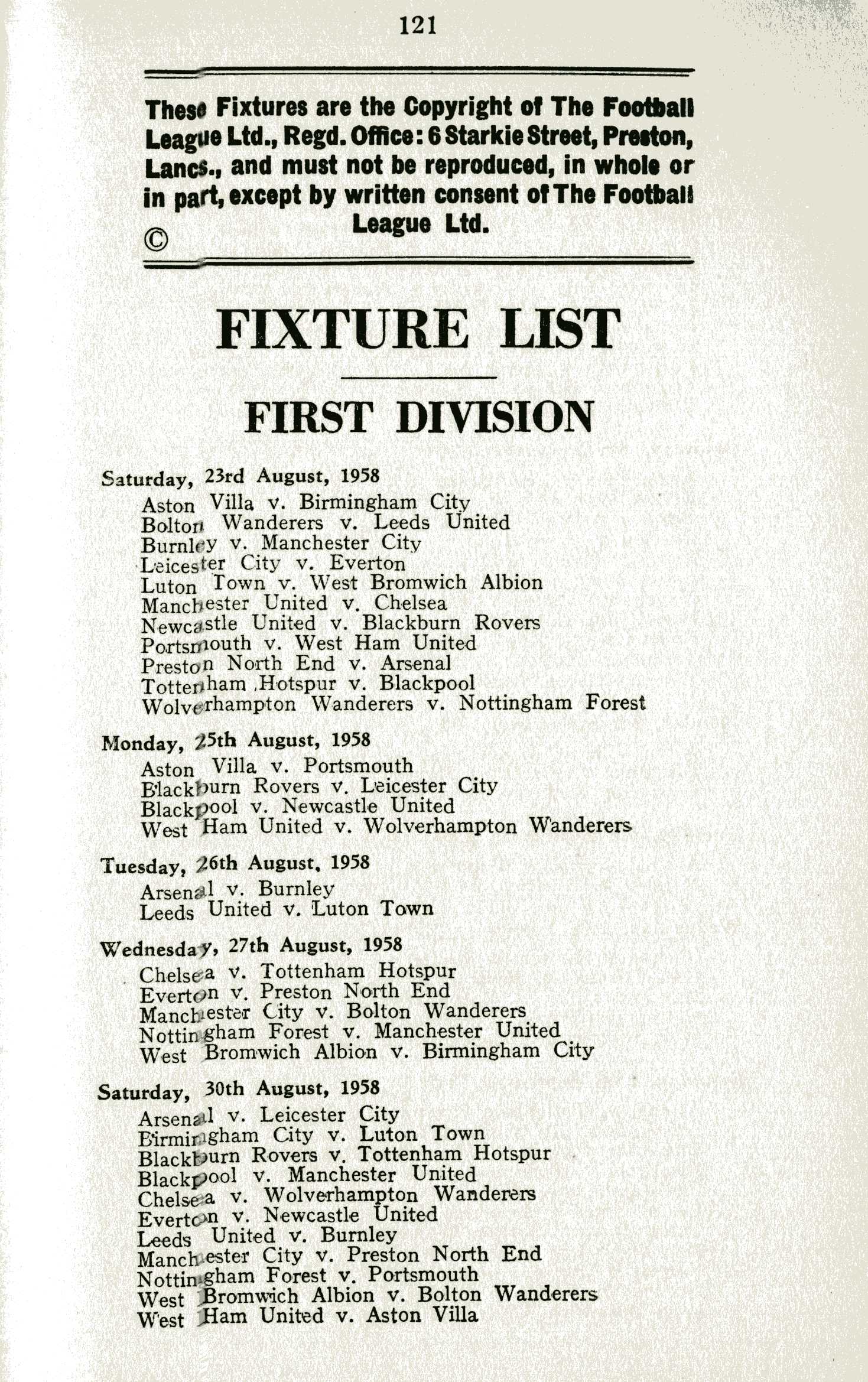

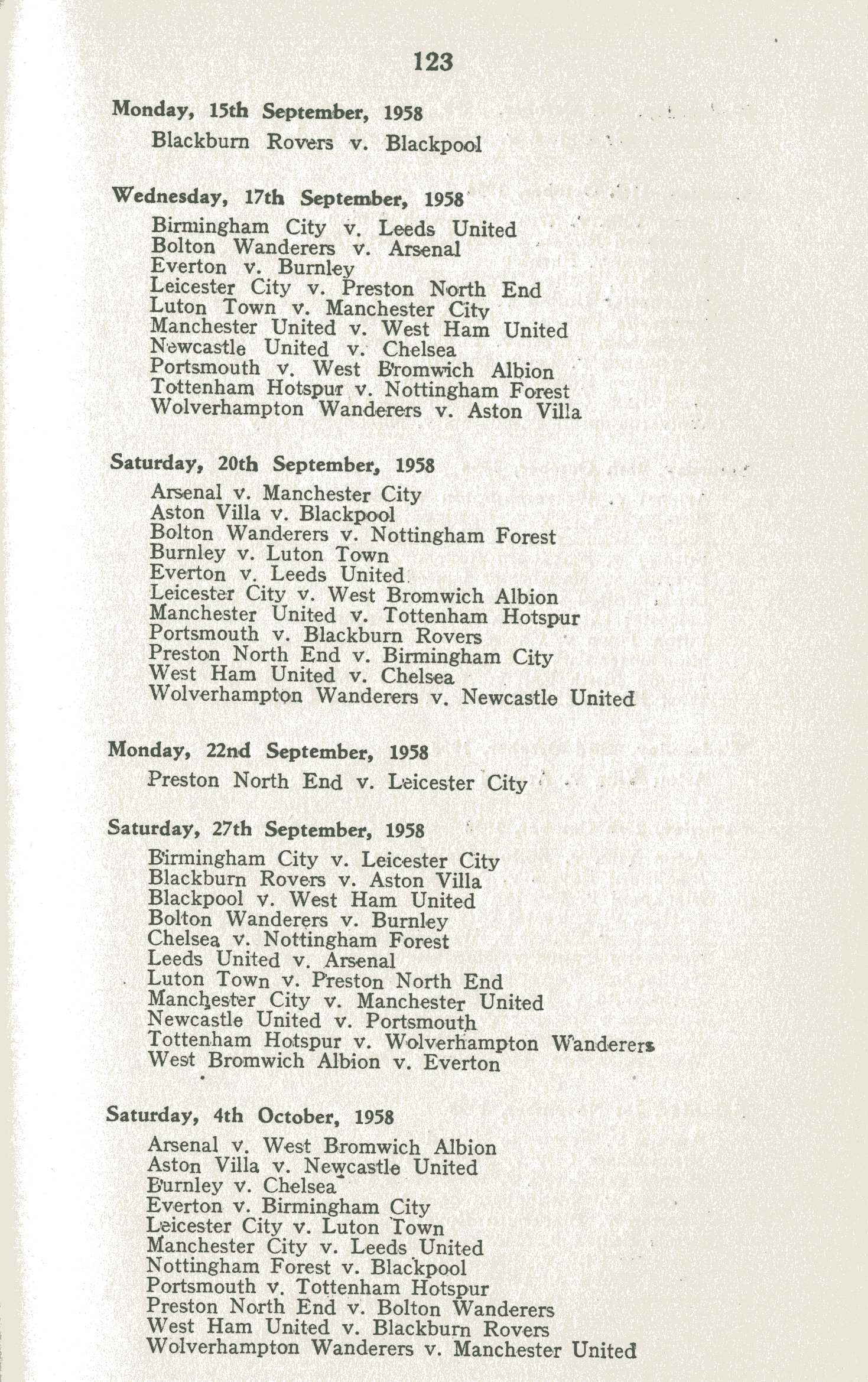

A writ issued in July 1958 (The Times, Oct 13, 1958, p 10d). The copyright action was brought against the largest member of the Pool Promoters Association, Littlewoods Pools Limited – which in 1958-9 took gross stakes of £43 million (compared with ll other pools companies, for whom the combined figure was £40 million: The Observer, May 22, 1960).. The remedies applied were a declaration of copyright in their 1958-9 fixture list; an injunction to restrain Littlewoods from reproducing the whole or any substantial part of the lists in their coupons, plus damages.

We have included here some images of the chronological lists litigated and compiled in the annual handbook published by the League that was mentioned in the case. That the League was ready to launch copyright action can be seen in the copyright notice inserted at the beginning of the list, informing users that “the Fixtures are the Copyright of the Football League, Ltd” and adding that they “must not be reproduced, in whole or in part, except by written consent of the Football League Ltd.”

Mr Justice Upjohn heard the case in the spring of 1959. The case was presented for the Football League by the Chancery silk, Sir Edward Milner Holland QC (1902-1969) and copyright specialist Francis Edmund Skone James, for the Football League. Skone James was, from 1927 through to 1948 the sole editor of the classic text originally authored by Walter Copinger (6th ed 1927, 7th ed, 1936, 8th ed 1948), and continued to co-edit the 9th ed, 1958 and the 10th ed 1965 with his [son?], Edmund Purcell Skone James,. (The Times, April 15, 1959, p. 3g). Counsel for Littlewoods, Kew Edwin Shelley QC, was a patent specialist, then editor of Terrell on patents (9th ed, 1951, 10th ed 1961).

A key witness was Harold Sutcliffe, the son of C.E. Sutcliffe, who now compiled the fixture list in the same manner as his father had before him. Mr Justice Upjohn observed that Harold Sutcliffe

"This work of preparing the list of fixtures is one that requires much skill and hard work. It is not possible to give effect to perfect pairing in every match nor to give effect to the wishes of every club in every particular; that would be beyond human ingenuity and skill, but Sutcliffe tries so far as his undoubted skill and ingenuity can do so to meet the wishes of all the clubs and to observe the essential of pairing.”

Upjohn J. thus held that the football fixture lists were “original literary works” because the “making of this list required painstaking accuracy and hard work”. Furthermore, he also held that there had been a copyright infringement. However, he refused to grant an injunction because the season was almost over.

Initially, Littlewoods proposed to appeal (Guardian, May 14, 1959), as Upjohn J had expected (in an aside he had said he quite expected the case to go to the House of Lords). However, before the appeal was heard, a settlement was negotiated. The four members of the Pools Promoters’ Association – (Littlewoods, Vernons, Copes and Murphy’s) agreed to pay ½ % of the gross stakes –some £245,00 per year - to the Football League and Scottish Football League: The Guardian, July 27, 1958. Zetters entered an independent agreement: Guardian, July 2, 1959. Only a few years later, competition within the pools companies would lead to further copyright litigation, between Ladbroke and William Hill.

The Internet revolution and the appearance of a new environment in which football fixtures and statistics could also be exploited for betting purposes brought a series of controversies that somehow echo this case:Football DataCo against (a) Brittens Pools Ltd reported in [2010] R.P.C. 17; (b) Yahoo! UK and Others [C-604/10, [2012] EUECJ C-604/10 and Sportradar, reported in [2013] EWCA Civ 27. Although the transnational aspect of these disputes and the new legislative framework for the protection of databases undoubtedly made them dissimilar to the case brought by the League against Littlewoods, some of the questions addressed in these new disputes resemble the ones put before Justice Upjohn six decades earlier. For instance, the possibility for football fixtures to attract copyright and the significance of systematic taking (week by week) for copyright infringement to be declared were issues already considered in 1959.

For a legal analysis of how these recent European cases may have questioned the UK approach, see Eleonora Rosati, “Towards an EU-wide copyright? (Judicial) pride and (legislative) prejudice” Intellectual Property Quarterly, 2013, 1, 47-68.

Twitter

Twitter Email

Email