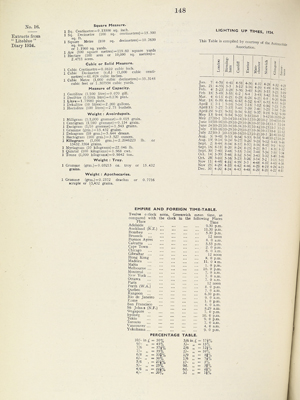

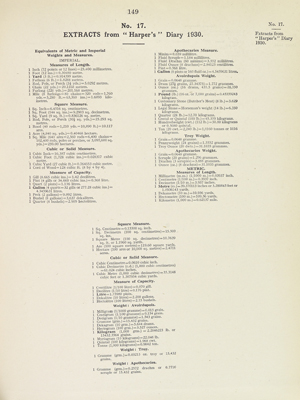

The case concerned two publishers of pocket diaries. The plaintiffs, Smythson, complained that the defendants, Cramp, had infringed their alleged copyright in their 1933 “Liteblue” diary. The main issue at stake lay in determining whether or not the selection and arrangement of certain tables of information printed in a pocket diary constituted a valid subject matter of copyright. Smythson’s “Liteblue” diary was first published in 1932 for 1933. The preliminary pages of the 1933 diary contained:- (i) a selection of “Days and Dates” for the year; (ii) Inland Postal Rates; (iii) Empire and Foreign Postal Information; (iv) Equivalents of Metric and Imperial Weights and Measures; (v) Light-Up Times for several named towns; (vi) Empire and Foreign Time Table (i.e., the equivalent time to noon at Greenwich for some thirty places); (vii)a Percentage Table. The plaintiffs based their claim to copyright upon the selection of these tables comprised in the “Liteblue” diary for 1933(see Image A), and that the infringement by the defendants consisted in printing and publishing this “copyright work” in their 1942 “Surrey Lightweight” Diary.

The case concerned two publishers of pocket diaries. The plaintiffs, Smythson, complained that the defendants, Cramp, had infringed their alleged copyright in their 1933 “Liteblue” diary. The main issue at stake lay in determining whether or not the selection and arrangement of certain tables of information printed in a pocket diary constituted a valid subject matter of copyright. Smythson’s “Liteblue” diary was first published in 1932 for 1933. The preliminary pages of the 1933 diary contained:- (i) a selection of “Days and Dates” for the year; (ii) Inland Postal Rates; (iii) Empire and Foreign Postal Information; (iv) Equivalents of Metric and Imperial Weights and Measures; (v) Light-Up Times for several named towns; (vi) Empire and Foreign Time Table (i.e., the equivalent time to noon at Greenwich for some thirty places); (vii)a Percentage Table. The plaintiffs based their claim to copyright upon the selection of these tables comprised in the “Liteblue” diary for 1933(see Image A), and that the infringement by the defendants consisted in printing and publishing this “copyright work” in their 1942 “Surrey Lightweight” Diary.

Smythson Ltd was incorporated in 1912, replacing a predecessor incorporated in 1907, which already specialised in the production of diaries. The first Smythson diary was produced in 1908, by the old company, and, in 1910, the name “Featherweight” was given to the diary. In 1912, Smythson produced a further diary called the “Wafer”. The “Wafer”, as its name suggests, was smaller than the “Featherweight” and was alleged to be the first pocket-sized diary. In 1930, Smythson began selling diaries in bulk to commercial firms. Firms would then distribute the diaries as gifts for advertising purposes. In 1932, the name “Liteblue” was given to these diaries. The “Liteblue” was similar in size to the “Wafer”, but was a cheaper production, designed for bulk purchase. Its contents and general get-up was based on the other Smythson diaries. Where necessary, these were brought up to date but remained substantially the same throughout.

G. A. Cramp & Sons Ltd, the defendants, were bookbinders, principally binding Bibles and Prayer Books and general ecclesiastical literature. The business was registered at Eveline Road, Mitcham, Surrey, and the trade name, Surrey Manufacturing Company used. At the time of trial, diary publishing accounted for about 10 per cent of their business profits. In oral evidence at trial, the managing director, Kenneth George Cramp, told the court that the company starting producing commercial gift diaries in 1926. However, no file copy could be produced to the court.

The defendants began binding dairies for plaintiffs in 1932, a business relationship which continued until 1941. In 1937, a former employer of Smythson, Mr Eckford, went to work as Cramp’s diary manager and salesman. In July 1937, Mr Frank Smythson, then managing director, wrote to Cramp & Sons about a circular letter which had been sent by Mr Eckford to a number of Smythson’s customers. In the letter, Mr Eckford refers to Smythson goods as being inferior to those manufactured and offered by Cramp. Kenneth Cramp, on being notified by Smythson’s solicitor of Mr Eckford’s letter, arranged to see Mr Smythson. During their meeting, Mr Cramp agreed to provide an undertaking that Cramp & Sons would not solicit Smythson’s customers by making “objectionable remarks” about their products. In oral evidence at trial, Mr Cramp purports that, following their meeting, the two “parted quite good friends”. Cramp’s written undertaking was later sent to Smythson, dated December 13th, 1937. By December 1939, Mr Eckford had left the employ of Cramp & Sons. Mr Smythson died in 1940.

On December 12th, 1941, Smythson issued their writ in the High Court in London claiming infringement of their alleged copyright and seeking an injunction, and damages for infringement and conversion of infringing copies. The case came before Mr Justice Uthwatt in the Chancery Division with evidence heard over a six day trial, commencing on October 21st, 1942.

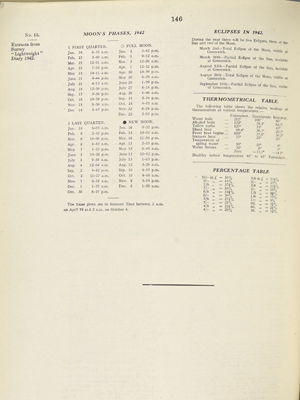

During the course of the trial, evidence was presented to the court that while an employee of Cramp & Sons, Mr Eckford had been placed in charge of the production of their 1938 “Surrey Lightweight” Diary. It was not disputed, that, in 1937, with the necessary calendar alteration and a few minor variations Mr Eckford copied seven printed tables in the plaintiff’s “Liteblue” diary 1933 and published them in the defendant’s diary. The information copied was carried on from year to year from the 1938 edition, subject to the necessary revisions (see Image B). Therefore, if the plaintiffs had any copyright in their seven tables, the defendants had infringed it. The question was whether the plaintiffs had any such copyright.

During the course of the trial, evidence was presented to the court that while an employee of Cramp & Sons, Mr Eckford had been placed in charge of the production of their 1938 “Surrey Lightweight” Diary. It was not disputed, that, in 1937, with the necessary calendar alteration and a few minor variations Mr Eckford copied seven printed tables in the plaintiff’s “Liteblue” diary 1933 and published them in the defendant’s diary. The information copied was carried on from year to year from the 1938 edition, subject to the necessary revisions (see Image B). Therefore, if the plaintiffs had any copyright in their seven tables, the defendants had infringed it. The question was whether the plaintiffs had any such copyright.

The principles of law to be applied to the issue were not in any doubt. Under section 1(1), of the Copyright Act 1911, copyright subsists ‘in every original literary ...work’, a literary work includes “compilations” (s.35(1)). The authoritative statement on the question of when a compilation might be entitled to protection as a literary work was considered that of Lord Atkinson in Macmillan & Co., Ld v K. & J. Cooper. Presiding in this case, he stated:

“What is the precise amount of the knowledge, labour, judgment or literary skill or taste which the author of any book or other compilation must bestow upon its compilation must bestow upon its composition in order to acquire copyright in it within the meaning of the Copyright Act of 1911 cannot be defined in precise terms. In every case it must depend largely on the special facts of that case, and must in each case be very much a question of degree.”

Mr Shelley KC, for the plaintiffs, submitted that the diary pages in the “Liteblue” diary were so arranged that the placing of days and dates had an unique and distinctive character, and that, though the information contained in the tables of information was public property, it had been selected from several sources, collated and arranged into tables by Mr Smythson. Moreover, Mr Shelley advanced an additional argument. He contended that section 6 (3) (b), of the Copyright Act 1911, created a presumption of originality in the plaintiff’s favour which had not been rebutted by the evidence. The paragraph relied on provides that when a work does not bear the author’s name, but the name of the publisher is indicated, then, unless the contrary could be proved, the latter would be presumed to be the owners of the copyright for the purpose of proceedings in respect of the infringement of copyright. Mr Shelley argued that this presumption extended not only to the question of title, but to the existence of copyright in the work.

For the defendants, Mr Pritt KC argued that there could be no copyright in the “Liteblue” diary, for it was in no sense a literary work and the mere arrangement of the days of the month in a particular layout could not make it so. The tables were no more than a commonplace selection of commonplace matter such as is found in all diaries of this sort. The selection of these precise items for inclusion involved no such “knowledge, labour, judgment or literary skill or taste” as would entitle the resultant selection to copyright. Moreover, the defendants were entitled to the protection afforded by section 8 of the Copyright Act 1911 because at the date of the infringement they were not aware and had no reasonable ground for suspecting that copyright existed in the work.

Mr Justice Uthwatt considered first the plaintiff’s argument on the true construction of section 6 of the Copyright Act, 1911. He held that the presumption related to title only, and merely:

“ removed the necessity of proving devolution of title to the copyright, if any, which exists in the work. It results from this reading of the section that the question of originality is not touched by the presumption.”

In considering the evidence put before him, as to the manner in which the work came into being, Uthwatt J. held that there could be no copyright in the compilation of tabulated information commonly found in diaries. He stated:

“I cannot see that the selection of lists and tables and the arrangement of the diary are anything other than a commonplace selection of gobbets of information and a common-place arrangement, neither of which involved any real exercise of knowledge, labour, judgment or skill.”

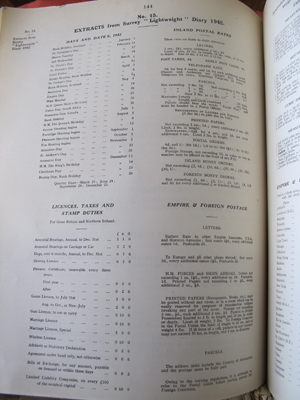

Uthwatt J based his decision on a number of factors. Firstly, the plaintiffs were unable to give any oral evidence directly bearing on the authorship, to show how or why the particular selection was made. Mr Frank Smythson, who was responsible for putting out earlier editions of the diaries, was dead and there were no grounds for inferring that the preparation of any one of the tables was the original work of Mr Smythson, or of anyone representing the plaintiffs. Uthwatt J drew attention to evidence which had been presented by counsel for the defendants that the table of equivalents of metric and imperial weights and measures appeared to have been copied from a Harper’s Diary 1930 edition, or was drawn from some source used by both Harper and the plaintiff (see Image C).

Uthwatt J based his decision on a number of factors. Firstly, the plaintiffs were unable to give any oral evidence directly bearing on the authorship, to show how or why the particular selection was made. Mr Frank Smythson, who was responsible for putting out earlier editions of the diaries, was dead and there were no grounds for inferring that the preparation of any one of the tables was the original work of Mr Smythson, or of anyone representing the plaintiffs. Uthwatt J drew attention to evidence which had been presented by counsel for the defendants that the table of equivalents of metric and imperial weights and measures appeared to have been copied from a Harper’s Diary 1930 edition, or was drawn from some source used by both Harper and the plaintiff (see Image C).

Secondly, Uthwatt J was satisfied on the evidence that the “Liteblue” contained only the sort of information normally found in diaries. He said that, “there is nothing distinctive in the selection which was made...or indeed remarkable in the lay-out of the Smythson diary”. In connection with this point, evidence was presented to the court of a further diary known as the “Pelham”. The “Pelham” diary had been printed and bound by Cramp & Sons since 1939, but its contents and lay-out were the sole responsibility of the manager of Boots, Mr. Harker Smith. Much of the printed matter, the type and lay-out were similar to the “Liteblue”. However, evidence was given by Mr Smith that he had been responsible for the matter and layout since 1923.

The plaintiffs appealed, and, on February 15th, 1943, the Court of Appeal, by a 2 to 1 majority reversed Uthwatt J. and held in favour of the plaintiffs. The Master of the Rolls, Lord Greene, thought that Uthwatt J. had taken too narrow a view:

“It seems to me clear that certain of the tables were original in the sense that they were arranged by somebody, and are not be found elsewhere than in the “Liteblue” diary save in the admitted copy made by the defendants... Although collections of tables of information are a common feature of diaries, diaries differ completely in type of table which the compilers think suitable. There is no common collection. The true inference appears to be that every person who publishes a diary exercises his own judgment in deciding what tables and what information will be of interest and use to purchasers of the diary, and in making that selection he has to consider not only that matter but also what space is available.”

Lord Greene M.R’s decision appears to be heavily influenced by the inequitable behaviour of Mr Eckford in copying the plaintiff’s diary in 1938. He continued:

“Now why did Mr Eckford copy the plaintiffs’ diary in 1938? The inference seems to me clear that he did it to save himself trouble. If he had to exercise independent judgment of his own and decide what were the tables which it would be useful to include, and had gone to the sources where the information was to be found, making abridgments where necessary, and selections where necessary, he would clearly, I think, have been put to considerable labour, and would have had to exercise skill and judgment of his own. Instead of doing that he appropriated the result of the plaintiffs’ work and copied direct their diary in its entirety.”

It is arguable that Lord Greene M.R. felt that the plaintiffs deserved to be protected from the defendant’s servant’s inequitable behaviour, and, perhaps, in the absence of an alternative remedy, copyright seemed to offer a method of protection.

Lord Justice Mackinnon, who arrived at the same conclusion, said:

“That the defendants have slavishly copied the printed matter in the plaintiff’s book is manifest. The only question therefore is whether the matter so copied is susceptible of being the plaintiff’s copyright. The matter copied is information as to various topics such as the complier of such a diary invariably prefixes to the pages of the diary proper. Information of this sort is, of course, open to all the world as part of the stock of common knowledge. The complier of this part of a diary is set two tasks: first the selection of the topics, and secondly the expression of the written matter on each topic.... What degree of labour and skill will suffice to create copyright in an original work must in every case be a question of fact. In the present case it is near the line, as is patent from the fact that I find myself in disagreement with Uthwatt J. and Luxmoore L.J, but, in my opinion, the plaintiffs are entitled to say that they have copyright in the eight pages of printed matter which the defendants appropriated, and therefore they are entitled to succeed.”

In his dissenting judgment, Luxmoore L.J. thought that in the absence of evidence, owing to the death of Mr Smythson, other than the existence of the tables of information as they appeared in the “Liteblue” diary for 1933, it was impossible for the plaintiffs to establish that the amount of knowledge, labour, judgment or literary skill or taste applied to the compilation of the tables and lists at the beginning of the “Liteblue” diary entitled the compilation to copyright. He said:

“I agree with the view expressed by Uthwatt J. that, looked at apart from any evidence, the compilation for which copyright is claimed is nothing more than a commonplace selection or arrangement of scraps of information, neither of which involved any real exercise of labour, judgment or skill.”

Moreover, Luxmoore L.J thought that Mr Shelley was pressed by the absence of the evidence to establish his case of originality that he had advanced with great ingenuity a subsidiary argument, that the plaintiffs were entitled under s. 6(3) of the Copyright Act 1911 to be presumed the owner of the copyright. Luxmoore L.J., in agreeing with Uthwatt J., found this argument to be unsound. Section 6(3) referred solely to the question of title and not to the question of the subsistence of copyright.

The Court of Appeal considered three subsidiary matters. Firstly, Mr Shelley submitted that copyright could exist in the diary as a whole, which fell into two parts. One was the collection of tables inserted at the beginning, and the other was the general arrangement and layout of the body of the diary – the way in which the days and dates were set forth, the space allotted for notes and memoranda, etc. Lord Greene M.R. held that, there was no copyright in the diary pages, or in the peculiar layout of such pages, but only in the collection of tables which the plaintiffs had selected and inserted in the beginning of their 1933 “Liteblue” diary. Nor did he think there was a separate copyright in each new edition of the diary, or in the annual work of bringing the tables up to date.

Finally, the respondents contended that they were entitled to the benefit of section 8 of the Copyright Act, 1911, exempting them as innocent infringers from any liability in damages. This proceeded on the basis that, since the person who originally copied the plaintiff’s diary was no longer in their service, and there was no evidence that anyone responsible for the edition which had given rise to Smythson’s complaint had any reason to suppose that it was copyright matter, or was aware of the existence of copyright, they were entitled to claim mitigation of the consequences of infringement. Mackinnon L.J., in considering the respondent’s argument, said that, although the meaning of the section was obscure, it did not introduce any exception to the rule that ignorance of the law is no excuse for the individual who is guilty of offending against it. Lord Greene M.R. thought that the defendants had misdirected themselves as to the law, and having come to the conclusion that the matter in the diary could not be the subject matter of copyright they made no inquiry as to the facts. They acted in ignorance to the law, and that could never be accepted as constituting an innocent infringer within the meaning of the section.

Cramp & Co appealed to the House of the Lords. In an unanimous judgment, handed down on June 21st, 1944, five judges reversed the decision of the Court of Appeal and restored the judgment of Mr. Justice Uthwatt, dismissing the claim.

The Lord Chancellor, Viscount Simon, in considering the test of originality, said:

“There would, indeed, as it seems to me, be considerable difficulty in successfully contending that ordinary tables which can be got from, or checked by, the postal guide or the Nautical Almanacs are a subject of copyright as being original literary work. One of the essential qualities of such tables is that they should be accurate so that there is no question of variation in what is stated... There is no room for taste and judgment. There remains, I agree, the element of choice as to what information should be given and the respondents contend that the test of originality is satisfied by the choice of the tables inserted. But the bundle of information furnished is commonplace information which is ordinarily useful and is at any rate to a large extent commonly found prefixed to diaries, and, looking through the respondents’ collection of tables, I have difficulty in seeing how such tables in the combination in which they appear in the respondents’ diary; there was no feature of them which could be pointed out as novel or specially meritorious or ingenious from the point of view of the judgment or skill of the compiler; it was not suggested that there was any element of originality or skill in the order in which the table are arranged. My own conclusion is that the selection did not constitute an original literary work.”

Lord Macmillan aptly summed up the test which the law applies to such cases:

“I do not doubt that, as the annuals of literature show, a high degree of knowledge and skill may be displayed and much labour and judgment expended in gathering from the wide fields of non-copyright material at the disposal of the public specialised collections of extracts designed to meet particular needs or particular tastes, but it must always be a question of degree. Not every compilation can claim to be original literary work even in the pedestrian sense attributed to these words by the law. Thus, to take a familiar example, it has been held by this House that to compile from the official time tables of the railway companies a local time table showing a selection of trains to and from a particular town is not to compose a work entitled to copyright. Such a compilation may be convenient and useful for the inhabitants of that town, but it does not require either such labour or such ingenuity in its preparation as to render to fit subject-matter for copyright: Leslie v J. Young & Sons”.

The House also considered two subsidiary arguments. Firstly, Mr Shelley’s argument for the respondents on the interpretation of s. 6(3) of the Copyright Act 1911 that it created a presumption of copyright in the respondents’ favour. In agreement with the Court of Appeal, none of the judges in the House of Lords acceded to his argument. The Lord Chancellor and Lord Macmillan both expressed the view that even if the burden of proof had been shifted, any presumption in favour of the plaintiffs (respondents in this action) of the existence of copyright was displaced on the facts of the case.

The other subsidiary point was that arising out of the defence under s. 8 of the Copyright Act 1911, which exempts an “innocent infringer” from liability in damages and cuts down the relief of a successful plaintiff to the sole remedy of an injunction. The Court of Appeal had held that the section had no application to a defendant who had copied on the erroneous assumption that the words copied were not by their nature the subject matter of copyright. There was, however, some expression of opinion by the House of Lords that it was a case in which, if the plaintiffs had succeeded in satisfying the onus of proof of originality, the respondents would have been entitled to the benefit of the section. Lord Macmillan, in his judgment, said he desired expressly to reserve his opinion as to whether Lord Green M.R. and Mackinnon, L.J were right in holding that the respondents were not entitled to claim mitigation of the consequences of infringement on the ground that they were not aware, and had no reasonable ground for suspecting, that copyright existed in the work.

Images supplied by Parliamentary Archives.

Twitter

Twitter Email

Email