The case involved the cartoonist, Bill Tidy (1933-), in his claim that the reproduction of his cartoon sketches of dinosaurs in reduced size constituted a distortion, or was otherwise prejudicial to his honour or reputation.

The case involved the cartoonist, Bill Tidy (1933-), in his claim that the reproduction of his cartoon sketches of dinosaurs in reduced size constituted a distortion, or was otherwise prejudicial to his honour or reputation.

Tidy, who was well-known for his sketches for the satirical magazines Punch and Private Eye, entered into a contract, between December 1991 and January 1992, with the Trustees of the National History Museum, the first defendant, to create a series of cartoons about dinosaurs. The contract entitled the museum to display copies of the cartoons during a proposed exhibition scheduled for 1995. Each cartoon produced by Tidy measured 420 millimetres by 297 millimetres. The copyright in the original drawings remained vested with Tidy.

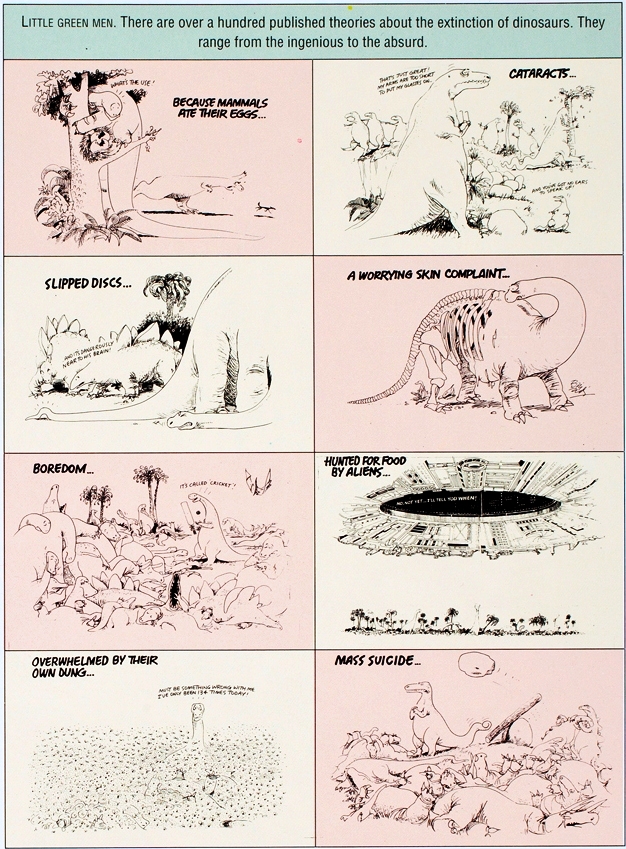

In May 1993, the second defendant published and distributed a book entitled, ‘The Natural History Museum Book of Dinosaurs’. The book contained reproductions of Tidy’s dinosaur cartoons, but the reproductions of eight of the relevant cartoons in the book were reduced in size to 67 millimetres by 42 millimetres. Moreover, the cartoons were given a background colouring of pink and yellow, whereas the original cartoons had been entirely in black and white.

Tidy, in an application for summary judgment, complained that the reproduction of the cartoons represented a breach of his copyright on two grounds. Firstly, he insisted, he had not consented to the reproduction. Further, he argued that the reproduction in the defendant’s book amounted to derogatory treatment of the cartoons within the meaning of section 80 (1) of the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988. In Tidy’s view, the reproduction of his images on a smaller scale detracted from the visual impact of the cartoons, made some of the captions difficult to read, and gave the impression that Tidy “could not be bothered” to redraw the cartoons in a size suitable for publication in the book.

The application came before Mr Justice Rattee on March 29th, 1995 in the Chancery Division of the High Court, London. The defence, filed on behalf of the Museum, initially did not admit to any breach of copyright. However, by the time Rattee J considered the matter, the defendant had admitted that reproducing the plaintiff’s cartoons in a book without his consent did represent a breach of copyright. Therefore, the sole issue for Rattee J to consider was whether the plaintiff should have summary judgment for a declaration that the reproduction of the cartoons in the reduced size format amounted to derogatory treatment of the plaintiff’s cartoons within section 80(1) of the 1988 Act.

Section 80(1) provides that:

‘The author of a copyright literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work... has the right in the circumstances mentioned in this section not to have his work subjected to derogatory treatment.’

For the purpose of this section, ‘treatment’ of a work means any ‘addition to, deletion from or alteration to or adaption of the work’.

It was not in dispute that the reproduction and reduced size of the cartoons amounted to ‘treatment’ of Mr Tidy’s work. The issue was whether or not that treatment was derogatory within the meaning given to that term in para. b of subsection (2) of section 80. To be derogatory, the treatment concerned – in this case, a reproduction of cartoons in reduced size in the second defendant’s book – must amount to a ‘distortion’ or ‘mutilation’ of the plaintiff’s work, or must ‘otherwise [be] prejudicial to the honour or reputation’ of the plaintiff’s work.

The plaintiff’s counsel, Ms (later Professor) Alison Firth, did not contend that the Book’s illustrations amounted to a mutilation, since these were exact reproductions, albeit in reduced dimensions, of Mr Tidy’s work. She did, however, contend that the reproduction amounted to a “distortion” of the work, or, alternatively, that it was “otherwise prejudicial” to the honour or reputation of Mr Tidy. Further, Ms Firth contended that a trial on this issue was unnecessary, as even a cursory examination of the reproductions would make it apparent that they represented a distortion of the plaintiff’s work, or were otherwise prejudicial to his reputation, and that there was no defence to the claim.

Mr Cunningham, counsel for the defendants, sought to have the application for summary judgment dismissed on procedural grounds, namely the failure by the plaintiff’s counsel to file an affidavit under the rules of the Supreme Court. Rattee J. found this matter irrelevant and was satisfied he could give judgment without the said affidavit.

In giving his judgment, Rattee J. refused the plaintiff’s application for summary judgment, explaining that he was far from satisfied that the reproductions amounted to a distortion of the drawings. He stated that:

“...simply looking at the book, although I can see, having regard to their size, the reproduced cartoons are not as effective in their impact on the eye as the full size originals, and although I can see that it is considerably more difficult to read some of the captions on some of them than in the original size, I am far from satisfied that it is clear beyond argument that the small size reproduction of the cartoons amounts in any way to a distorting of the original.”

Moreover, in considering counsel’s alternative claim that even if there was no distortion, it should be abundantly clear on the evidence before the court (the originals and reproduction) that the reproduction was prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the plaintiff, Rattee J was also unconvinced. He stated that:

“I personally find it difficult to see how I could possibly reach the conclusion that the reproduction complained of is prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the plaintiff without having the benefit of cross-examination of any witnesses giving evidence on that point.”

Rattee J referred to the Canadian case, Snow v The Eaton Centre 70 C.P.R. 105 which considered a comparable section referring to treatment of a work in a way prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author. The presiding judge, O’Brien J. said that the words "prejudicial to honour and reputation involved a certain subjective element or judgment on the part of the author, so long as it was reasonably arrived at". Rattee J. held that, before accepting the plaintiff’s view that the reproduction in the book complained of was indeed prejudicial to his honour or reputation, he would have to be satisfied that the view was one that was reasonably held, which "inevitably involves the application of an objective test of reasonableness". He concluded by stating that:

“It is sufficient for the purposes of disposing of the present summons that I am far from satisfied that there is no possible defence to the claim made by the plaintiff. It seems to me that there is a possible defence, and I need put it no higher for present purposes, on the grounds that in fact the reputation of the plaintiff would not be harmed one whit in the mind of any reasonable person looking at the reproduction of which he complains.”

Sophie Eastwood, June 2015

Image supplied by UCL Media and Photography Department

Twitter

Twitter Email

Email