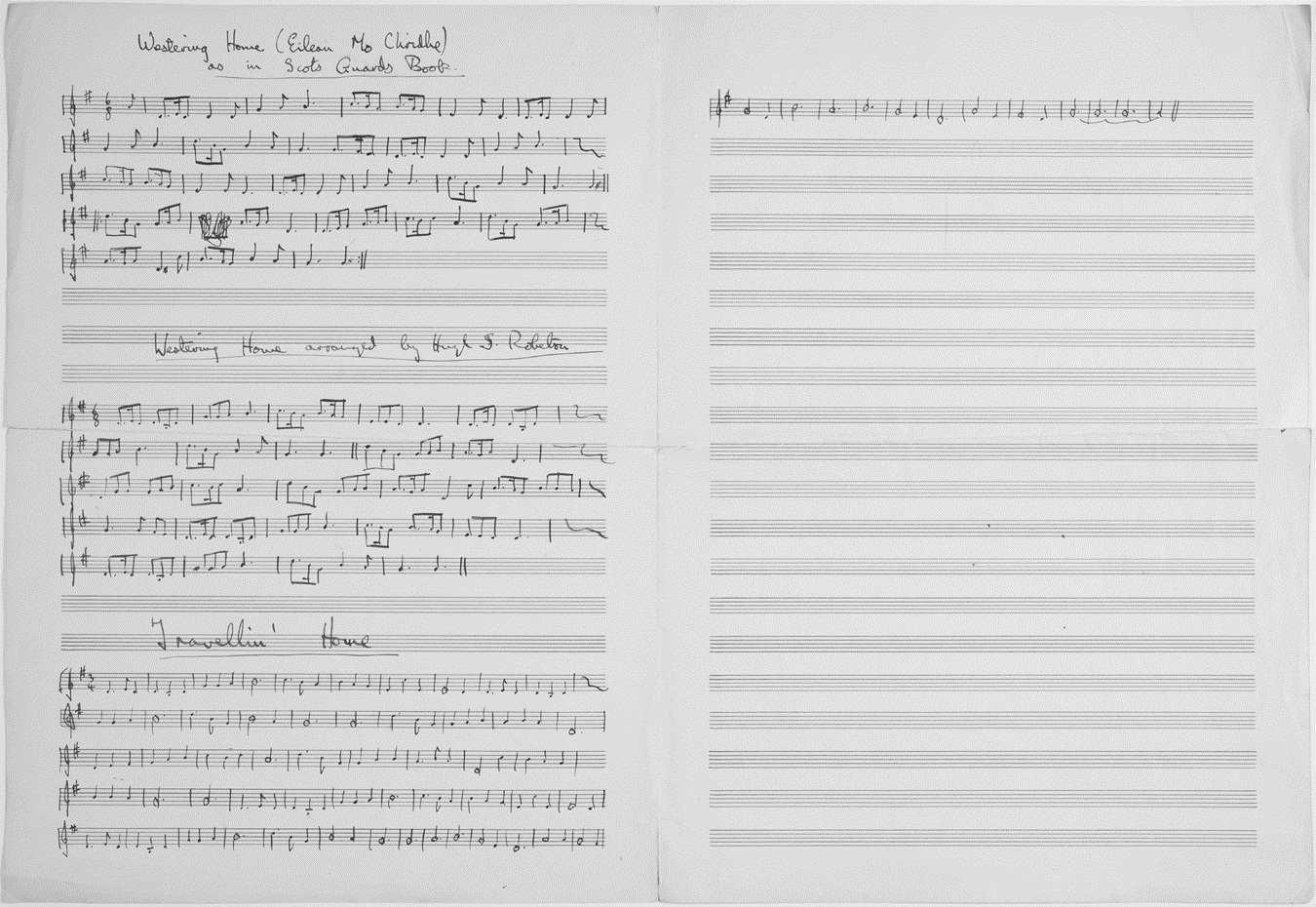

Image courtesy of Gerald Pointon.

This action was brought by Lady Helen Roberton and others against Harry Lewis (trading as Virginia Music) and others for copyright infringement of "Westering Home", a song composed/arranged by Sir Hugh S. Roberton (1874-1952), who had died a few years before the trial. The accused song was “Travellin’ Home”, a record sung by Dame Vera Lynn that had sold 75,000 copies within a few days of release.

It was also the first case for the éminence grise in the history of British music copyright, the composer Geoffrey Bush (1920-1998), who was then appointed by the defendants as an expert witness. Bush worked closely with Gerald Pointon, a solicitor’s articled clerk who had read music and law at Cambridge. On the expert's advice, Pointon went to the British Museum library in search of material for the defence. There he was given the task of looking for a number of folk songs and jigs that Bush had named, in the hopes of identifying `likely non-copyright sources of the musical ideas' that the defendants had been `accused of having stolen'. The material found at the library helped the defendants ground their case in the possible links between traditional music and the plaintiffs' song. Bush and the junior clerk made the material comparable by transcribing both the folk songs and the litigated music. A central part of this strategy was to transpose the various songs into the same key, making it easier to see the visual similarities. We have included here the manuscript paper the defendants used. Instead of juxtaposing the works on separate pages, they sandwiched the plaintiffs' song between the defendants' work and traditional songs, and transferred all of them onto a special A3 sheet of paper. The textual assemblage hinted at the temporal order between the songs: the traditional music was situated first, as if it was the source of all the rest, leaving the defendants' song to be placed below.

In June 1960, Mr Justice Cross gave judgment for the defendants. He decided that the Roberton estate had failed to show that the Dame Vera Lynn and her co-defendants had made direct or indirect use of Roberton's composition. Bush modestly acknowledged that their victory had less to do with his advice and more to do with the impact that the testimony of the pipe-major and other bagpipers from the Scots Guards had on the judge.

For a more detailed analysis of the context in which this case emerged, see Jose Bellido “Popular Music and Copyright Law in the Sixties” Journal of Law and Society, vol. 40, n. 4, December 2013. pp. 570-95.

Twitter

Twitter Email

Email