Images i, ii, iii and iv supplied by Parliamentary Archives; images v, vi and vii courtesy of "Grace's Guide to British Industrial History"; images viii and xi courtesy of Roy Morton.

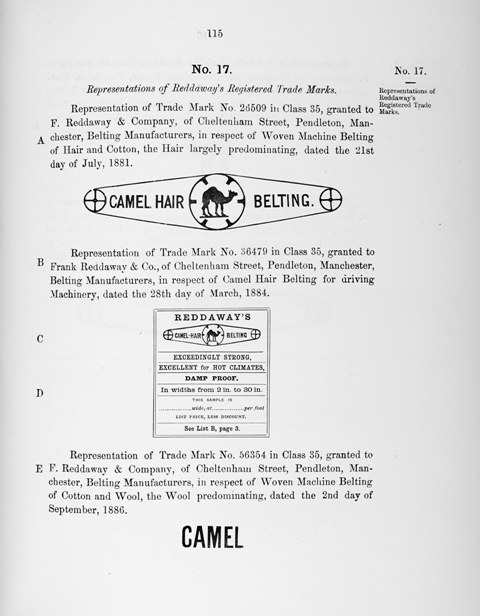

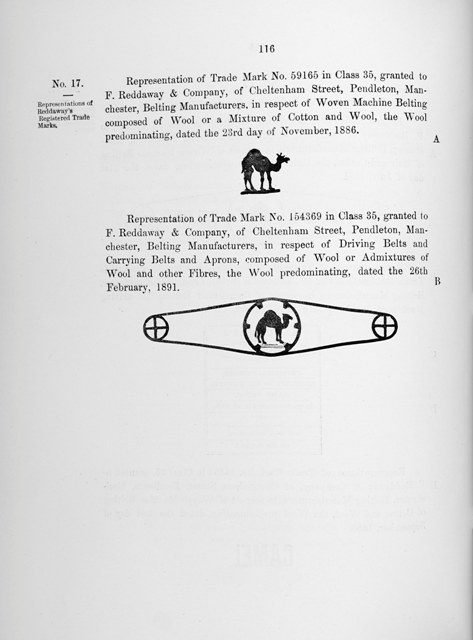

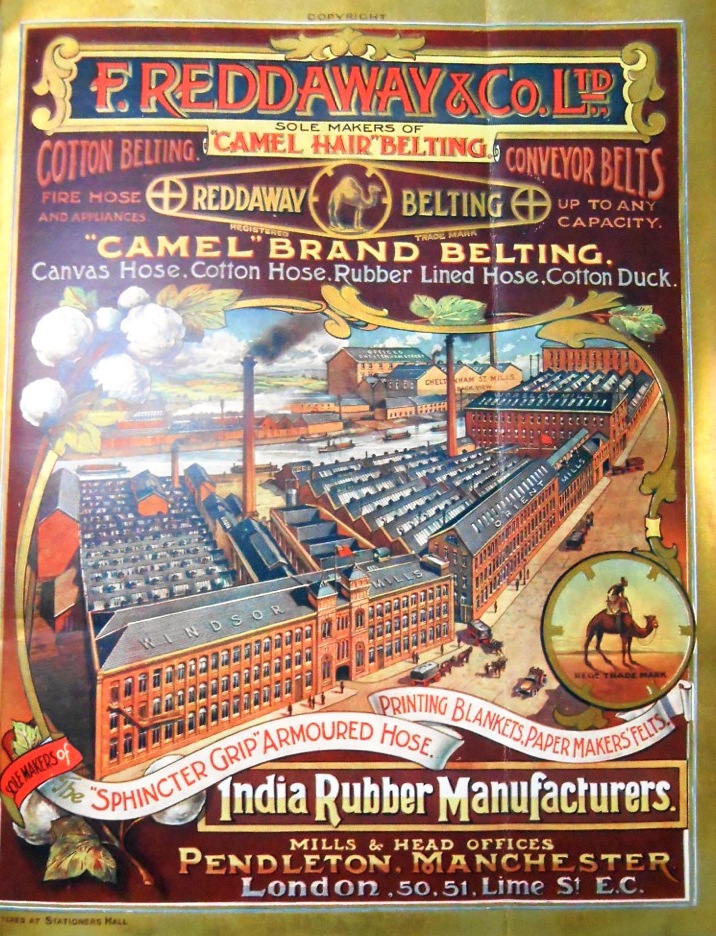

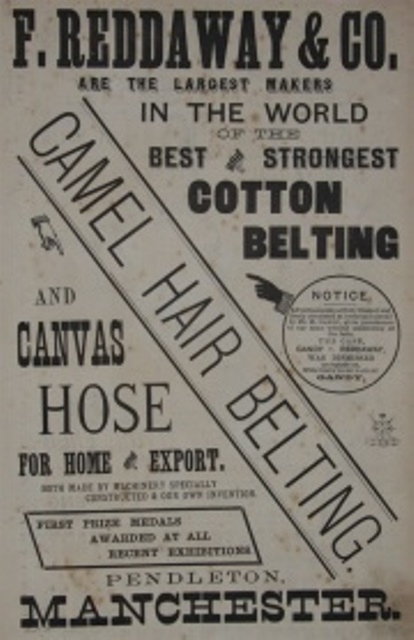

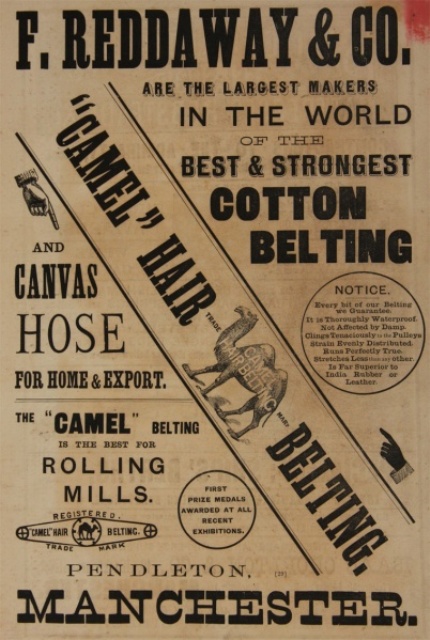

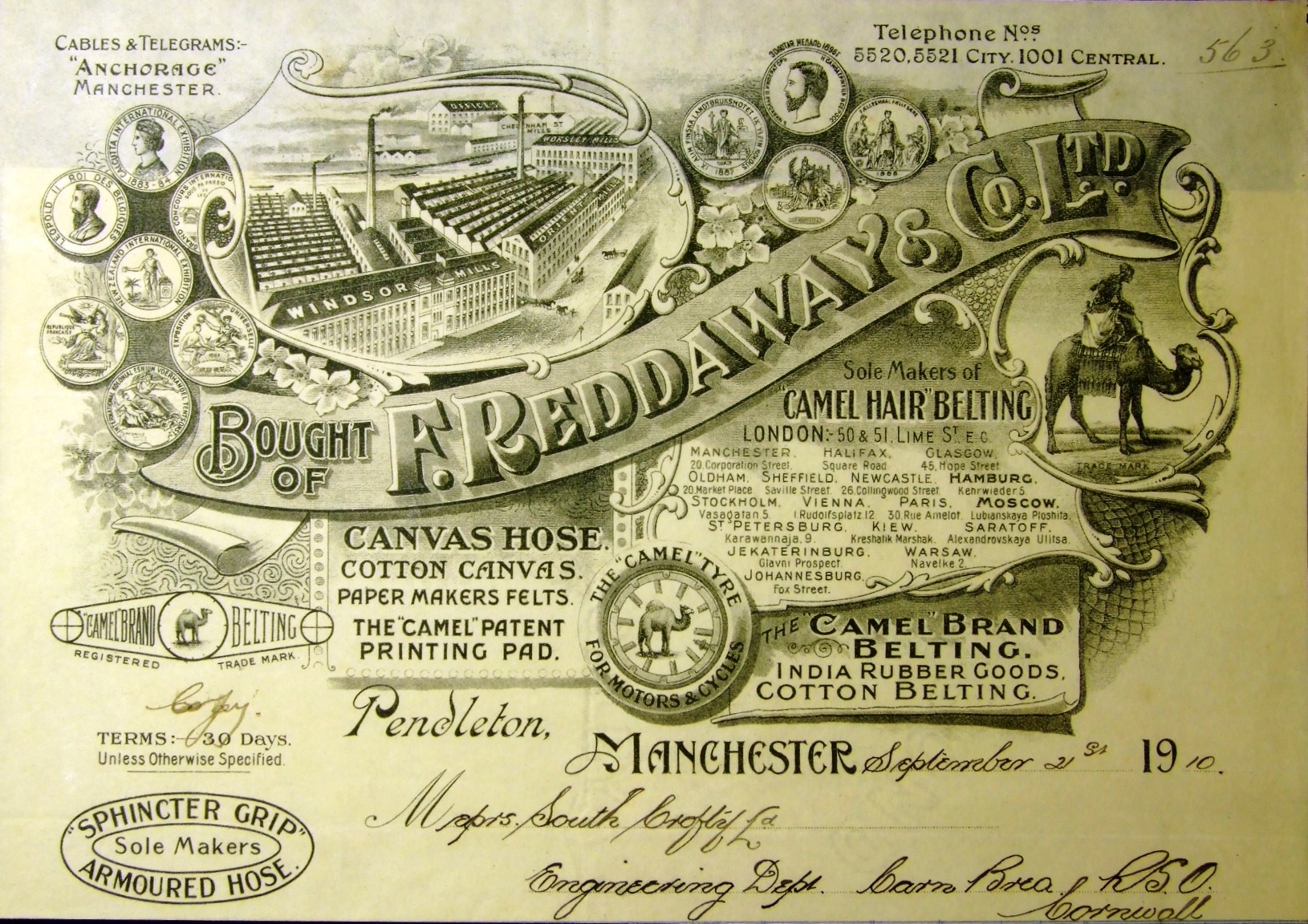

In Reddaway v Banham, the plaintiff was a manufacturer of belting for use in machinery, with considerable custom in India and elsewhere abroad. Much belting was made from leather, but animal fibre worked better in hot and dry countries. Reddaway’s belting had initially been made from wool, but the purchasers seemed to be rather indifferent as to its particular constituents. From 1879 Reddaway referred to it as “camel-hair belting”, while other trader’s called their belting by names such as yak, buffalo, llama and crocodile. It registered various trade marks (depicted), though there was no suggestion in the case that these had been used by the defendant. Before bringing this case, Reddaway had already succeeded in an action against the Stockport Paste and Lace Co (7 September 1886) and, having been non-suited by Cave J in an action against the Bentham Hemp Sinning Co succeeded in convincing the Court of Appeal (A.L. Smith LJ, dissenting) that the question of whether Bentham’s use of “Bentham Camel-hair belting” should have been put to the jury([1892] 2 QB 639). At least as early as 1886, it had issued notices warning traders that it would bring actions against others using the term “camel-hair belting”. See The Standard, Sept 21, 1886.

The defendant, an employee of Reddaway, left and set up in competition in the belting market. It began selling its belting as “Arabian belting”, but in 1891 started using the term “camel-hair belting.” Indeed, it guaranteed that its belting was “better than that commonly called ‘camel hair belting’”. By this time, both the plaintiff and defendant’s belting did in fact comprise a substantial amount of camel hair.

The plaintiff sought an injunction, and the case was tried in Manchester before Collins J. and a jury (Manchester Weekly Times, July 27, 1894). Collins J summed up, and put various questions to the jury, which struggled with the case, twice returning to the courtroom. Ultimately, it found that the term “camel-hair belting” in fact was understood to refer to the plaintiff’s belting, and thus in using that term that the defendant was passing off its product as and for that of the plaintiff. Reddaway advertised the success widely in the newspapers of the day.

The defendants appealed, successfully, to the Court of Appeal ([1895] 1 QB 286). There Lord Esher MR, Lopes and Rigby LJJ agreed that no trader should be prevented by injunction from telling in the course of business “the simple truth”.

The plaintiffs appealed, now with the benefit of one of the leading silks of the day, John Fletcher Moulton QC (1844-1921), later Lord Moulton, as well as Herbert Henry Asquith QC (1852-1928), later to be Prime Minister. The House of Lords (Lords Halsbury, Herschell, MacNaghten and Morris) unanimously reversed the decision of the Court of Appeal, restoring the first instance judgment. Their Lordships emphasised that the principles of the law – the “common law of trade marks” – were clear, and that their application was a matter that turned on the facts. The evidence demonstrated that there was material on which the jury could have found that “camel-hair belting” referred to the product as manufactured by the plaintiff. The Court of Appeal was wrong in its understanding that this prevented the Defendant from telling the truth – in the specific circumstances where the words had a “secondary signification” it was not “telling the truth” to refer to its product as “camel-hair belting”. Their Lordships emphasised the limitations inherent in the injunction, clearly taking the view that if Banham called its belting by some other name but indicated it was made from camel hair there would be no infringement. Indeed, Lord Morris indicated that the failing was not to add “as manufactured by Banham.”

One commentator Ernest A Jelf, ‘Piracy of Trade Names and Descriptions’, (1898) 23 (4) Law Magazine and Review 299-309, “rejoiced” at the decision. However, a closer examination reveals that his reaction must not be assumed to be disinterested. Jelf had earlier represented Reddaway in the 1892 proceedings against the Bentham Hemp Spinning Company in the Court of Appeal.

The case has come to stand for the proposition that descriptive terms can acquire secondary meaning, and thus become the basis for an action in “passing off”.

Images i and ii

Images iii and iv

Images v, vi and vii

Images viii and xi

Twitter

Twitter Email

Email